The Individual in Communication Research: Part IV

This is the fourth part of a series that traces the history of how the idea of the "individual" has been understood in the history of media research. In a way, this part recounts American social science reaching some form of theoretical climax. The theories born in this particularly fecund period of positivist social science research, have grown to become some of the best known and established theories in the literature, with an enduring legacy of widespread application.

Read part 1 here.

Read part 2 here.

Read part 3 here.

-

The Individual in Dominant Media Theories

Following the criticisms raised against the “minimal effects” era, there was renewed enthusiasm about finding “not so minimal effects” of media. Shanto Iyengar and colleagues for example, did precisely that. They conducted experimental studies to assess the impact of television programs on individuals and found evidence of how “profoundly” individuals were affected by what they saw (Iyengar, Peters, & Kinder, 1982). The “agenda setting theory” was one of the big breakthroughs of the body of research of this age. In their now classic paper, Maxwell McCombs and Donald Shaw conducted correlational studies and claimed (thereby defining the concept of agenda setting) that while media did not tell individuals what to think, they are “stunningly successful” in telling them what to think about (1972). Of course, these were still intuitions based on pure correlations, but they would be experimentally proven years later (King, Schneer, & White, 2017).

Many other theories blossomed during this period, which became dominant over the following years. Priming theory for instance, based off of Iyengar et al.’s work (1982) posited that media provide a context for the public discussion of an issue by stimulating mental images in the minds of the individuals in an audience. Framing theory, drawing on Erving Goffman’s work (1974) was based on the premise that media provided a certain environment or focus while telling a story, and this focus influenced how individuals received it.

With these two eras of communication research (“minimal effects”, and “not so minimal effects”) juxtaposed next to and, often overlapping with each other, there came a slew of studies that claimed to find evidence for one, and not the other, and vice versa. The “problem of the individual” was now caught between a paradox of “massive media impact” on the one hand and “the myth of massive media impact” (McGuire, 1986; Zaller, 1996) on the other. Most of the research during this period relied either on surveys or on experiments, and as more and more scholars unearthed increasing amounts of evidence of the effect of messages on individuals, a certain peculiarity seemed to emerge.

This peculiarity was summed by the sociologist Seymour Lipset, working on similar studies with his colleagues, albeit a few years earlier: “As long as we test a program in the laboratory, we always find that it has great effect on the attitudes and interests of the experimental subjects. But when we put the program on as a regular broadcast, we then note that the people who are most influenced in the laboratory tests are those who, in a realistic situation, do not listen to the program. The controlled experiment always greatly overrates effects, as compared with those that really occur…” (Lipset, Lazarsfeld, Barton, & Linz, 1954). Carl Hovland, a psychologist working at Yale, set about trying to solve this paradox. He hypothesized that the discrepancy in results was largely attributable to two kinds of factors: “one, the difference in research design itself; and, two, the historical and traditional differences in general approach to evaluation”(1954). He considered exposure as an example of the former, explaining how surveys collect responses from individuals who have been exposed to a piece of communication over a prolonged period of time in completely natural contexts, whereas experiments are generally only able to record short-term exposure effects in artificial laboratory settings. Of the latter factor, he gave the example of the “size of the communication unit” that is studied: an “entire program of communication” in surveys versus “some particular variation in the content of the communication” in experiments. Hovland then concluded that “no contradiction” exists between the results obtained in survey research and experimental studies. In fact, as he went on to say, the “seeming divergence can be […] accounted for on the basis of a different definition of the communication situation […] and differences in the type of communicator, audience, and kind of issue utilized” (Hovland, 1954). In other words, the media seemed to be having short term effects on individuals in the laboratory. Out in the real world, the effects were far less pronounced. While Hovland’s hypothesizing was sound, it did not quite hold water in the face of the dominant theories (agenda setting, priming, framing etc – which we have already discussed) that emerged later. In fact, the other great “massive effects” theory was based entirely on the premise that media effects are long term. George Gerbner and colleagues (1980) studying such long term effects of media exposure on individuals crucially found evidence, that more the time people spend watching television and “living” in the television world, “the more likely they are to believe social reality aligns with reality portrayed on television” (Riddle, 2009). They called this the “cultivation theory”.

The “problem of the individual” – at least in so as far as the effects of media on individuals were concerned, had therefore reached some form of an equilibrium. There was evidence of short term media effects on individuals in controlled environments, but not in the real world. But over time, the effects did seem to grow and accumulate, and in the end, as the dominant theories of the age seemed to claim, they had proved to be substantially “massive” indeed.

Read the final part here.

-

References

Gerbner, G., Gross, L., Morgan, M., & Signorielli, N. (1980). The “Mainstreaming” of America: Violence Profile No. 11. Journal of Communication, 30(3), 10–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1980.tb01987.x

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Cambridge, MA, US: Harvard University Press. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/record/1975-09476-000

Hovland, C. I. (1954). Reconciling Conflicting Results Derived from Experimental and Survey Studies of Attitude Change. In W. Schramm & D. Roberts (Eds.), THE PROCESS AND EFFECTS OF MASS COMMUNICATION (pp. 495–515). University of Illinois.

Iyengar, S., Peters, M. D., & Kinder, D. R. (1982). Experimental Demonstrations of the "Not-So-Minimal" Consequences of Television New

King, G., Schneer, B., & White, A. (2017). How the news media activate public expression and influence national agendas. Science (New York, N.Y.), 358(6364), 776–780. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao1100

Lipset, S. M., Lazarsfeld, P. F., Barton, A. H., & Linz, J. (1954). The psychology of voting: An analysis of political behavior. In Handbook of social psychology (pp. 1124–1175).

McCombs, M., & Shaw, D. (1972). The Agenda-Setting Function of Mass Media. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 36(2), 176–187.

McGuire, W. J. (1986). The myth of massive media impact: Savagings and salvagings. Public Communication and Behavior. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-531956-0.50007-X

Riddle, K. E. (2009, May 21). Cultivation Theory Revisited: The Impact of Childhood Television Viewing Levels on Social Reality Beliefs and Construct Accessibility in Adulthood.

Zaller, J. (1996). The Myth of Massive Media Impact Revived: New Support for a Discredited Idea. In S. Mutz & Body (Eds.), Political Persuasion and Attitude Change (pp. 17–78). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Read part 1 here.

Read part 2 here.

Read part 3 here.

-

The Individual in Dominant Media Theories

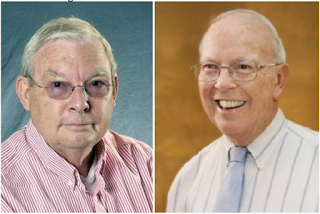

Following the criticisms raised against the “minimal effects” era, there was renewed enthusiasm about finding “not so minimal effects” of media. Shanto Iyengar and colleagues for example, did precisely that. They conducted experimental studies to assess the impact of television programs on individuals and found evidence of how “profoundly” individuals were affected by what they saw (Iyengar, Peters, & Kinder, 1982). The “agenda setting theory” was one of the big breakthroughs of the body of research of this age. In their now classic paper, Maxwell McCombs and Donald Shaw conducted correlational studies and claimed (thereby defining the concept of agenda setting) that while media did not tell individuals what to think, they are “stunningly successful” in telling them what to think about (1972). Of course, these were still intuitions based on pure correlations, but they would be experimentally proven years later (King, Schneer, & White, 2017).

Many other theories blossomed during this period, which became dominant over the following years. Priming theory for instance, based off of Iyengar et al.’s work (1982) posited that media provide a context for the public discussion of an issue by stimulating mental images in the minds of the individuals in an audience. Framing theory, drawing on Erving Goffman’s work (1974) was based on the premise that media provided a certain environment or focus while telling a story, and this focus influenced how individuals received it.

|

| Donald Shaw and Maxwell McCombs source: https://seer.ufrgs.br/intexto/article/viewFile/46390/32217 |

This peculiarity was summed by the sociologist Seymour Lipset, working on similar studies with his colleagues, albeit a few years earlier: “As long as we test a program in the laboratory, we always find that it has great effect on the attitudes and interests of the experimental subjects. But when we put the program on as a regular broadcast, we then note that the people who are most influenced in the laboratory tests are those who, in a realistic situation, do not listen to the program. The controlled experiment always greatly overrates effects, as compared with those that really occur…” (Lipset, Lazarsfeld, Barton, & Linz, 1954). Carl Hovland, a psychologist working at Yale, set about trying to solve this paradox. He hypothesized that the discrepancy in results was largely attributable to two kinds of factors: “one, the difference in research design itself; and, two, the historical and traditional differences in general approach to evaluation”(1954). He considered exposure as an example of the former, explaining how surveys collect responses from individuals who have been exposed to a piece of communication over a prolonged period of time in completely natural contexts, whereas experiments are generally only able to record short-term exposure effects in artificial laboratory settings. Of the latter factor, he gave the example of the “size of the communication unit” that is studied: an “entire program of communication” in surveys versus “some particular variation in the content of the communication” in experiments. Hovland then concluded that “no contradiction” exists between the results obtained in survey research and experimental studies. In fact, as he went on to say, the “seeming divergence can be […] accounted for on the basis of a different definition of the communication situation […] and differences in the type of communicator, audience, and kind of issue utilized” (Hovland, 1954). In other words, the media seemed to be having short term effects on individuals in the laboratory. Out in the real world, the effects were far less pronounced. While Hovland’s hypothesizing was sound, it did not quite hold water in the face of the dominant theories (agenda setting, priming, framing etc – which we have already discussed) that emerged later. In fact, the other great “massive effects” theory was based entirely on the premise that media effects are long term. George Gerbner and colleagues (1980) studying such long term effects of media exposure on individuals crucially found evidence, that more the time people spend watching television and “living” in the television world, “the more likely they are to believe social reality aligns with reality portrayed on television” (Riddle, 2009). They called this the “cultivation theory”.

|

| George Gerbner source: https://ascla.asc.upenn.edu/communications-scholars-history-project/ |

The “problem of the individual” – at least in so as far as the effects of media on individuals were concerned, had therefore reached some form of an equilibrium. There was evidence of short term media effects on individuals in controlled environments, but not in the real world. But over time, the effects did seem to grow and accumulate, and in the end, as the dominant theories of the age seemed to claim, they had proved to be substantially “massive” indeed.

Read the final part here.

-

References

Gerbner, G., Gross, L., Morgan, M., & Signorielli, N. (1980). The “Mainstreaming” of America: Violence Profile No. 11. Journal of Communication, 30(3), 10–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1980.tb01987.x

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Cambridge, MA, US: Harvard University Press. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/record/1975-09476-000

Hovland, C. I. (1954). Reconciling Conflicting Results Derived from Experimental and Survey Studies of Attitude Change. In W. Schramm & D. Roberts (Eds.), THE PROCESS AND EFFECTS OF MASS COMMUNICATION (pp. 495–515). University of Illinois.

Iyengar, S., Peters, M. D., & Kinder, D. R. (1982). Experimental Demonstrations of the "Not-So-Minimal" Consequences of Television New

King, G., Schneer, B., & White, A. (2017). How the news media activate public expression and influence national agendas. Science (New York, N.Y.), 358(6364), 776–780. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao1100

Lipset, S. M., Lazarsfeld, P. F., Barton, A. H., & Linz, J. (1954). The psychology of voting: An analysis of political behavior. In Handbook of social psychology (pp. 1124–1175).

McCombs, M., & Shaw, D. (1972). The Agenda-Setting Function of Mass Media. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 36(2), 176–187.

McGuire, W. J. (1986). The myth of massive media impact: Savagings and salvagings. Public Communication and Behavior. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-531956-0.50007-X

Riddle, K. E. (2009, May 21). Cultivation Theory Revisited: The Impact of Childhood Television Viewing Levels on Social Reality Beliefs and Construct Accessibility in Adulthood.

Zaller, J. (1996). The Myth of Massive Media Impact Revived: New Support for a Discredited Idea. In S. Mutz & Body (Eds.), Political Persuasion and Attitude Change (pp. 17–78). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Comments